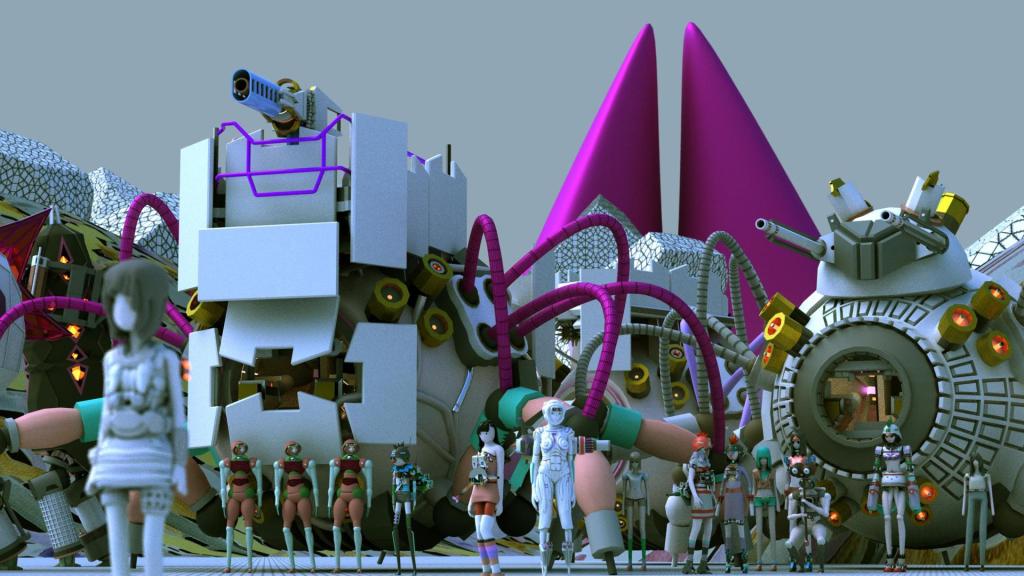

Imagine a somewhere that is not here. Imagine there are crab robots (with pinchers, naturally), and hard-edge robots, and both think they are the ‘humans’ by which I can only assume they believe themselves to be the dominant species, the apex predators, so of course the only solution is to continually invade each other’s planets and try to kill each other off. But in a war of robot versus robot, there are no quick winners, and the robots are eventually exhausted. The hard-edge robots form weird jellyfish cocoons that ultimately destroy the crab robots’ planet.

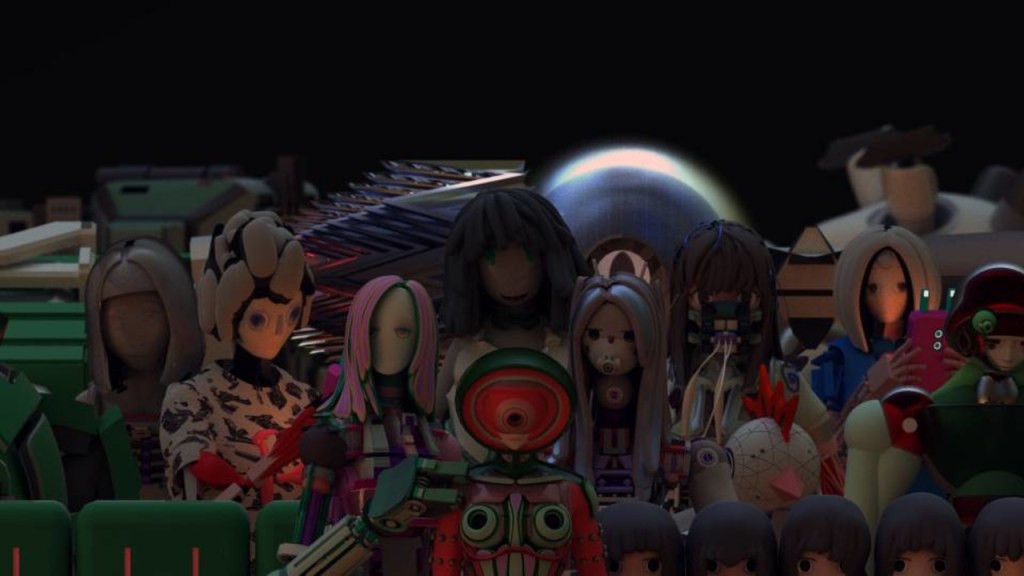

I can’t logically or lucidly explain why, but this is somehow the precipitating factor in a chicken larva not reaching adulthood and instead of hiding away in a cave, he wanders the planet wearing robot armour. He’s a mystery and a marvel, but he’s the least of your worries. There are robot ladies, big eyes, doll heads, chicken heads, creepy-crawlies, and things that look vaguely Star Wars-like. Robots continue to fight, so I can only assume they continue to battle for supremacy.

I understand how this sounds. You can’t make sense of this because I can’t make sense of it because, I suspect, it doesn’t wholly make sense. It’s like my 5 year old niece Ella, distracted by someone having fun on the trampoline without her, is relating a story to her 7 year old cousin, Jack. Jack is hopped up on sugar and has to pee, but does his best to understand, and then to recount the story to Xi Chen over a Zoom call during which Jack’s first priority is showing off all his trophies and medals. And then Xi Chen, whose first language is not English, animates the thing to the best of his ability but without asking a single clarifying question. It’s delirious stuff. A lot of the robots look like weird hybrids that a child’s imagination might produce given a box of crayons and enough blank paper – a mix of their limited but enthusiastic understanding of robots, and limited by their artistic abilities.

Xi Chen’s minimalist narration, an imperfect translation, is like toneless poetry (perhaps the kind of poetry written and recited by a robot?). They are rare interjections between dialogue-free scenes scored by the kind of beep-boops kids imagine robots voice, and the phaser sounds they make with their sticky mouths while play-shooting each other in the backyard.

Chicken of the Mound is undoubtedly odd and a little austere, but it’s like taking a ride on the magic school bus into a child’s imagination, where all things are possible, few things make sense, and everything can be turned into either a gun or a robot, or better yet, can transform between the two.