Say his name: Michael Brown.

Michael Brown had graduated high school just 8 days before the police shot him dead. He was planning to study heating and air conditioning repair at a technical college just two days later. Instead, an altercation with officer Darren Wilson, just 90 seconds from start to finish, led to Wilson discharging 12 bullets, 6 of which hit Brown, the last of which resulted in his death. Eye witnesses share conflicting accounts of what happened, but some are certain that Brown took the shots to his front while raising his hands in surrender and saying “Hands up, don’t shoot”. Michael Brown, completely unarmed, lay dead in the street, where his body remained for over four hours.

In the wake of Brown’s murder, protests, both peaceful and violent, continued for more than a week in Ferguson, and the police department’s response was botched, criticized for the tactless insensitivity of their highly militarized response. A grand jury failed to indict Wilson, adding injury to injury and reinforcing a divide in Ferguson based on the shade of one’s skin.

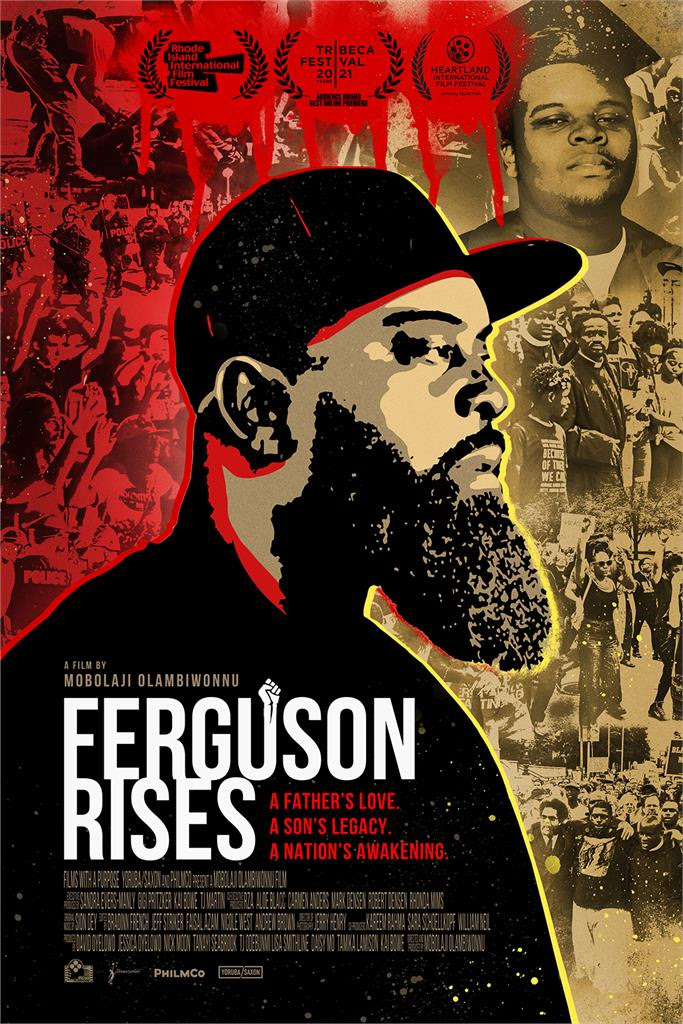

This documentary, by director Mobolaji Olambiwonnu, revisits the residents of Ferguson, a suburb of St. Louis, 7 years later. Michael Brown’s death – the murder of a Black body by a white and racist police officer – was sadly one of many, but his was a rallying point, igniting protests against police racism and brutality in Protests erupted in 170 cities across the U.S., including Seattle, New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago. But for Ferguson, it was different. It was personal. Missouri was the last state to abolish slavery, and the aftereffects of that oppression are still felt today. While white residents of Ferguson watched protests turn to riots, they expressed disbelief, and disapproval. But Brown’s death and subsequent treatment wasn’t a surprise to Ferguson’s Black community. Darren Wilson wasn’t one bad apple; the entire Ferguson PD was institutionally racist, routinely violating the rights of Black citizens.

Though the Black Lives Matter movement that has sprung up as a result of all these protests does have some white support in Ferguson, there are a number of white people still firmly on the wrong side of right. Brown’s mother and father will tell you what it feels like to live in a community divided over your son’s death. His friends will tell you what it’s like to drive by the spot where he was gunned down. Protesters will tell you what it was like to get on a plane and fly back in time, coming home to a town in Missouri where a white police force was brutalizing Black weeping mothers, shooting tear gas at people filled with righteous anger, using rubber bullets against people trying to express their horror, their abhorrence, their shock, their sorrow.

Many voices contribute to Ferguson Rises, and themes of strength and resilience seem to create a pattern. Black Americans may have suffering and oppression in their DNA, but they’ve got determination in their souls.

I knew this documentary would be an emotional watch, but it feels essential to return to the scene of the crime with a clear head in the pursuit of truth, and perhaps more importantly, real change. We have so little to offer Brown in exchange for his life – this feels like the least we can do.