I mean, who’s NOT excited to see a film adapted from a 784 page, Pulitzer-prize winning novel about a missing piece of art? Sean Taylor, that’s who. He did, however, make use of the film’s 147 minute run time to have a hearty nap. Hands lightly clasped, mouth totally agape, he slept, and he slept hard, for 60 of the film’s first 65 minutes. So when he did wake up, I wondered what the point was in staying. Surely he was lost. Surely there would be no rejoining the movie at this point.

But the truth is, wide awake as I was and always had been, I wasn’t any more into it. And yes, I had read Donna Tartt’s novel, which has been bowing my bookcase ever since.

The Goldfinch is about a little boy who visits a museum with his mother, who then perishes when the museum is bombed in a terrorist attack. Having survived the bombing, young Theo (Oakes Fegley) wanders around the ruins, searching for his mother, until an old man stops him, and with his dying breath, implores him to take a painting, Fabritius’ The Goldfinch.

Basically orphaned, Theo is sent to live with classmate’s family (Nicole Kidman plays the mother). He befriends the old man’s business partner, Hobie (Jeffrey Wright) and another young survivor, a cute redhead named Pippa, who sustained brain damage in the attack. But just as he’s maybe settling into this new, motherless life, his deadbeat dad (Luke Wilson) shows up, with a surprise girlfriend (Sarah Paulson) in tow, and whisks him off to live in a deserted Vegas suburb of foreclosed homes. His only friend is a boy named Boris (Finn Wolfhard), who’s got some questionable habits, though not nearly as objectionable as his dad’s, as it turns out.

Cut to: adult Theo (Ansel Elgort) is an antiques dealer, working with Hobie in New York City, trying his best just to cope with the lingering effects of the attack, trying hard not to be held hostage by the trauma. He’s held onto this painting, a very historied and valuable painting, all these years, secretly of course, allowing the rest of the world to believe this priceless artifact was destroyed in the bombing along with so much else. But that is not the case.

Can you imagine what this painting might represent to a young orphaned boy, having saved it from the very same rubble in which his mother’s body lay? Director John Crowley cannot. In 2.5 hours, the painting is not a symbol of hope, or a replacement parent, or the receptacle of grief and loss. It’s just a dead thing underneath a kid’s bed, as if it means nothing. In fact, the movie itself means nothing, but it takes an agonizingly long time establishing this nothingness. On and on, with lots of things happening yet none of it finding meaning. And worse yet, it finds no emotional connection, nor does it appear to even look for it. And when you’re talking about childhood trauma and absentee parents and feelings of dread and loneliness – well, you’ve got to be pretty bad at your job not to even accidentally stumble upon some kind of feeling.

The painting The Goldfinch is about how we preserve meaningful bits of our lives and our culture, but the movie The Goldfinch is about how some things are destined to be forgotten.

There’s occasionally a little tension between the brothers because in order to make their arrangement work, they have to live by certain rules. And as you might guess, Jonathan’s a better rule follower than is Jon. When Jon breaks a cardinal rule, ie, gets a girlfriend, the two start to pull apart, and while distance between siblings is usually a normal thing, between these two it’s going to start to get very, very complicated.

There’s occasionally a little tension between the brothers because in order to make their arrangement work, they have to live by certain rules. And as you might guess, Jonathan’s a better rule follower than is Jon. When Jon breaks a cardinal rule, ie, gets a girlfriend, the two start to pull apart, and while distance between siblings is usually a normal thing, between these two it’s going to start to get very, very complicated. unlikeable kid, and Grace-Moretz simply gets assigned the not-fully-realized female costar who heals his sadness by touching his penis. It’s not remotely their fault but November Criminals is maybe the most undercooked movie I’ve ever seen – like, on a scale from rare to well-done, it’s a bloody, oozy, thoroughly blue kind of undercooked that’s bound to give you worms. I’ve read the novel upon which it is based and half-remember it, and even that half-memory is more fulsome than the script for this thing, which feels like it’s missing about 75% of its content and 100% of what would make it understandable or good. The film offers up a small slice of the story, with an inadequate beginning and hardly any end, and such an abbreviated middle you’ll wonder if perhaps we’re still in the opening credits. But while the movie needs at least another two hours in order to tell its story, the mere thought of having to sit through a single moment more than its 85 minute run time is upsetting. This film never justifies any reason for its existence and wastes every frame of its film.

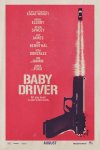

unlikeable kid, and Grace-Moretz simply gets assigned the not-fully-realized female costar who heals his sadness by touching his penis. It’s not remotely their fault but November Criminals is maybe the most undercooked movie I’ve ever seen – like, on a scale from rare to well-done, it’s a bloody, oozy, thoroughly blue kind of undercooked that’s bound to give you worms. I’ve read the novel upon which it is based and half-remember it, and even that half-memory is more fulsome than the script for this thing, which feels like it’s missing about 75% of its content and 100% of what would make it understandable or good. The film offers up a small slice of the story, with an inadequate beginning and hardly any end, and such an abbreviated middle you’ll wonder if perhaps we’re still in the opening credits. But while the movie needs at least another two hours in order to tell its story, the mere thought of having to sit through a single moment more than its 85 minute run time is upsetting. This film never justifies any reason for its existence and wastes every frame of its film. Darling (Eiza Gonzalez), Griff (Jon Bernthal), Buddy (Jon Hamm), and my personal favourite, Bats (Jamie Foxx), personal motto: “I’m the one with mental problems in the group. Position taken.” GUYS, HE’S NOT KIDDING.

Darling (Eiza Gonzalez), Griff (Jon Bernthal), Buddy (Jon Hamm), and my personal favourite, Bats (Jamie Foxx), personal motto: “I’m the one with mental problems in the group. Position taken.” GUYS, HE’S NOT KIDDING. Wright is a phenomenal writer, and Baby Driver is just as quippy and quotable as any other in his oeuvre. The music jangles, sometimes wildly incongruous to what’s developing on screen, sometimes deliciously ironic, but it stitches the film together between Wright’s explosive action sequences. Wright’s films are always kinetic. His own exuberance for film making comes across on the screen, is barely contained by it, in fact.

Wright is a phenomenal writer, and Baby Driver is just as quippy and quotable as any other in his oeuvre. The music jangles, sometimes wildly incongruous to what’s developing on screen, sometimes deliciously ironic, but it stitches the film together between Wright’s explosive action sequences. Wright’s films are always kinetic. His own exuberance for film making comes across on the screen, is barely contained by it, in fact.