In the mid-70s, photographer Cynthia MacAdams collected pictures of women, determined that feminism made them look different, distinct. Could the difference be observed on film? Her book of photographs immortalized an awakening, a second wave of feminism wherein women were shaking off their cultural expectations, shedding the shackles of their pasts, and stepping forward with new purpose.

40 years later, as MacAdams’ work is being exhibited, film maker Johanna Demetrakas tracks down many of the women featured in the work, including Jane Fonda, Funmilola Fagbamila, Gloria Steinem, Lily Tomlin, Margaret Prescod, Phyllis Chesler, and Judy Chicago and asks them about our continued need for change. Personally, seeing all these knowing eyes staring out at me, I feel galvanized.

40 years later, as MacAdams’ work is being exhibited, film maker Johanna Demetrakas tracks down many of the women featured in the work, including Jane Fonda, Funmilola Fagbamila, Gloria Steinem, Lily Tomlin, Margaret Prescod, Phyllis Chesler, and Judy Chicago and asks them about our continued need for change. Personally, seeing all these knowing eyes staring out at me, I feel galvanized.

Together they discuss employment, motherhood, abortion, choice, and the state of feminism today.

Jane Fonda says “I’ve only known for 10 years that ‘no’ is a complete sentence. That gave me pause. Don’t you love it when a book or movie reaches out, past the page or screen, and just touches you? This film is ripe for that, although it’s crazy that this brand new, just-released film already feels a little dated – in this #metoo, Trumped up era, feminism’s fourth wave is moving necessarily quicker than ever.

One thing I felt just a teensy bit gratified about is that this film devotes a small amount of time to address intersectional feminism and the ways in which historic feminism failed to include women of colour and other minorities. ‘Feminism’ has mostly meant white feminism, and white feminists have asked women of colour to somehow divorce themselves from their other concerns, as if they ever could. Race and gender must go together for WOC, and and we can’t properly call for advancement or equality of women without bringing all women along – queer women, trans women, women of every class and colour. This documentary acknowledges the deficits but doesn’t begin to delve into them – we’ll need many more documentaries to cover the complexities of black feminism.

Most of all, I am struck by so many notable women trying to reclaim the feistiness of their youth – not the righteous anger of their 20s or the organized action of their 30s, but the freedom of being a little girl, before any gender expectations have fully settled. Many seemed to hope age would help them reclaim that feistiness, but I wondered what it might be like if we never lost it to begin with.

serious child, and then a teenager with no patience for small talk. She learned some valuable lessons from her mother before losing her at a tender age. She went to Harvard Law, where she had to justify taking a seat away from a man. She met her husband, Marty, who admired her intelligence during a time when men were meant to dominate their spouses. She finished law school as a mother and a caretaker to her husband, who was stricken with cancer. Long before she was known to her country, she was known to friends and family as dedicated, hard-working, and tough.

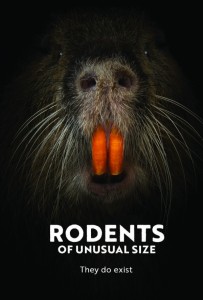

serious child, and then a teenager with no patience for small talk. She learned some valuable lessons from her mother before losing her at a tender age. She went to Harvard Law, where she had to justify taking a seat away from a man. She met her husband, Marty, who admired her intelligence during a time when men were meant to dominate their spouses. She finished law school as a mother and a caretaker to her husband, who was stricken with cancer. Long before she was known to her country, she was known to friends and family as dedicated, hard-working, and tough. In North America, the nutria’s only predators were humans. Without hunting, the nutria have multiplied terribly. Now this invasive species has overrun the land, its destructive eating and burrowing habits eroding coastline and eating up swamp land valuable for its protection against hurricanes.

In North America, the nutria’s only predators were humans. Without hunting, the nutria have multiplied terribly. Now this invasive species has overrun the land, its destructive eating and burrowing habits eroding coastline and eating up swamp land valuable for its protection against hurricanes.

Aboriginal people have been through a lot, historically, and still. Snatching children from out of their homes is among the most destructive of them. It breaks down their culture, their language, their family ties. It robs them of identity.

Aboriginal people have been through a lot, historically, and still. Snatching children from out of their homes is among the most destructive of them. It breaks down their culture, their language, their family ties. It robs them of identity. because it was difficult, or because he was unsure. He’d quit because he couldn’t reconcile the two halves of himself: the need to be strong AND be a woman. In his male skin, he needed to be the biggest, the most muscular, but as a woman he wanted to be petite. When he cut weight, dieted and stopped lifting, he deprived himself of his friends, his support system, the world he knew and the lifestyle he loved. Muscles were a security blanket of sorts. It’s hard to let those go.

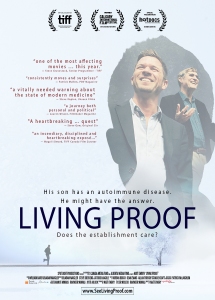

because it was difficult, or because he was unsure. He’d quit because he couldn’t reconcile the two halves of himself: the need to be strong AND be a woman. In his male skin, he needed to be the biggest, the most muscular, but as a woman he wanted to be petite. When he cut weight, dieted and stopped lifting, he deprived himself of his friends, his support system, the world he knew and the lifestyle he loved. Muscles were a security blanket of sorts. It’s hard to let those go. naturally, he developed a diet for his son to follow. Matt eats unprocessed food – no gluten, no dairy – mostly fruit, veg, and lean meats. And since MS occurs more often in northern countries, like Canada, he takes a big ole dose of Vitamin D, like sunshine in a bottle. Yes, it’s a strict diet and requires constant preparation and vigilance. But if you’ve known someone cut down by MS, their bodies just literally abandoning them, you’d probably find such a possibility to be suitably motivating. And thanks to this lifestyle, Matt is still symptom-free, TWENTY YEARS after diagnosis. He has never taken any medication, but he has had a procedure called CCSVI – many people with MS have significant blockages in their jugular vein, which means not enough blood flows through to the brain.

naturally, he developed a diet for his son to follow. Matt eats unprocessed food – no gluten, no dairy – mostly fruit, veg, and lean meats. And since MS occurs more often in northern countries, like Canada, he takes a big ole dose of Vitamin D, like sunshine in a bottle. Yes, it’s a strict diet and requires constant preparation and vigilance. But if you’ve known someone cut down by MS, their bodies just literally abandoning them, you’d probably find such a possibility to be suitably motivating. And thanks to this lifestyle, Matt is still symptom-free, TWENTY YEARS after diagnosis. He has never taken any medication, but he has had a procedure called CCSVI – many people with MS have significant blockages in their jugular vein, which means not enough blood flows through to the brain. about it. It’s a documentary about two guys who discover, quite by accident, that they are twins, separated at birth. They were both adopted and had no idea they had a look-alike brother until mutual friends confused them when they both wound up at the same college, which is amazing enough. Their story goes national: it’s the feel-good story of the year, two 19 year old boys jubilantly reunited. And of the millions who catch sight of their front-page story is a third identical stranger. They are not twins, but triplets.

about it. It’s a documentary about two guys who discover, quite by accident, that they are twins, separated at birth. They were both adopted and had no idea they had a look-alike brother until mutual friends confused them when they both wound up at the same college, which is amazing enough. Their story goes national: it’s the feel-good story of the year, two 19 year old boys jubilantly reunited. And of the millions who catch sight of their front-page story is a third identical stranger. They are not twins, but triplets. Lee’s flair for the dramatic meant he put on a damn good fashion show. Between his theatrical catwalks and his astonishing creations, he made a name for himself very quickly, very young. London loved to call him their own fashion bad boy, but he was nearly rejected by couture’s real epicentre, Paris, for being of the wrong cut. He was crass, he was lower class. He didn’t look the part or dress the part. Luckily fashion icon Isabella Blow discovered him, and through her, so did the world.

Lee’s flair for the dramatic meant he put on a damn good fashion show. Between his theatrical catwalks and his astonishing creations, he made a name for himself very quickly, very young. London loved to call him their own fashion bad boy, but he was nearly rejected by couture’s real epicentre, Paris, for being of the wrong cut. He was crass, he was lower class. He didn’t look the part or dress the part. Luckily fashion icon Isabella Blow discovered him, and through her, so did the world.