The Killing of Kenneth Chamberlain should truthfully be titled The MURDER of Kenneth Chamberlain, and I’m pretty sure everyone involved in this film hears the correct word shouted over the one that’s used every time it’s pronounced. The film does the shouting for them, of course, leaving little (no) doubt in anyone’s mind who watches it. Kenneth Chamberlain, a Black man, was murdered by the police. It is such a familiar refrain by now that it may seem redundant to make yet another film – but that’s exactly the point. These stories need to be told, heard, and shared until actual changed is effected. Kenneth Chamberlain was an old man in his bed when the police came knocking on his door. This is his story.

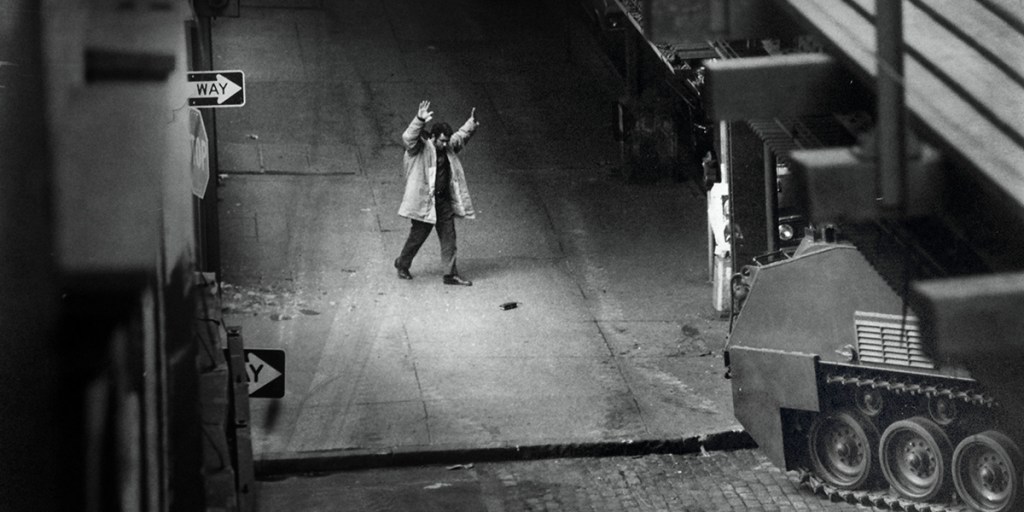

On a November night in 2011, Kenneth Chamberlain rolled over in his sleep and accidentally triggered his life alert button. The police showed up to his apartment in White Plains NY’s public housing do a wellness check around 5:30am. Rousing him from his bed, Kenneth was confused as he fumbled for his hearing aids. He was a retired Marine struggling with bipolar disorder; he was listed as ’emotionally disturbed’ by the police dispatch but in fact he wore the life alert for a heart condition. He refused to let the cops in but verbally assured them that he was fine and the button was pressed accidentally. The cops would not leave. Having assessed his neighbourhood as predominantly poor and Black, they were furious to not be let in, and wanting to teach him a lesson, they mused he might be hiding a meth lab, or a dead prostitute. Kenneth held his ground, growing increasingly agitated by the insistent banging and attempts to push their way in. Keeping the door firmly locked, Kenneth placed panicked calls to the life alert agency, pleading for his safety. Overhearing the police intrusion, the woman on the other end does everything in her power to call off the cops, but no matter what she or Kenneth, or Kenneth’s family do, the cops will not back down.

How do things go from a wellness check to gunning an old man down in just 90 minutes? Frankie Faison as Kenneth paints the troubling picture of yet another innocent Black man murdered by the police. The lengths the police will go to in order to murder him are astounding. While not a documentary, it almost watches like one, determined not to stray from the truth, which was recorded in its entirety by Kenneth’s staying on an open line with his life alert company. For some this will be old news, and for others eye-opening, but either way, this is must-watch viewing.