Detroit, 1967: a veritable race riot is boiling over the streets of the inner city. Buildings are on fire, stores are looted. Cops are on edge and are arresting any black person they see. The force is 93% white; 45% of those working in black neighbourhoods were considered to be “extremely anti-Negro” and an additional 34% were “prejudiced.” Charges of police brutality are abundant. Precincts overflow with black bodies.

On the night of July 25, police converge on the Algiers motel, allegedly because a sniper might be in or around the building. The motel’s 12 occupants are rounded up, interrogated, badly beaten, and humiliated by Detroit PD, Michigan State police, and the National Guard. At the end of the night, three black teenagers are left dead, killed by police.

Why? How?

Director Kathryn Bigelow presents a harrowing, claustrophobic rendition of these events, so tense and brutal that people walked out of the screening we attended. Other than Detroit being extremely difficult to watch, there are some problems with the film:  Bigelow’s treatment of the subject is at a pretty cold remove, for example. And I for one felt it was just too long. The film could have ended when the last person leaves the motel, but instead it follows the white police officers who were charged with felonious assault, conspiracy, murder, and conspiracy to commit civil rights abuse. The courtroom scenes are a long, drawn-out denouement that don’t quite jibe with the first two thirds of the film. That said, I still feel like Detroit is an extremely effective film.

Bigelow’s treatment of the subject is at a pretty cold remove, for example. And I for one felt it was just too long. The film could have ended when the last person leaves the motel, but instead it follows the white police officers who were charged with felonious assault, conspiracy, murder, and conspiracy to commit civil rights abuse. The courtroom scenes are a long, drawn-out denouement that don’t quite jibe with the first two thirds of the film. That said, I still feel like Detroit is an extremely effective film.

First, because it’s so timely. Watching those cops get off scot-free despite confessions, and then be congratulated for beating murder charges that were well-deserved, is infuriating, and familiar. This is not “history,” not when there are unarmed black children being gunned down by the people paid to protect them to this very day. It’s an uncomfortable reminder that in the past 50 years, we’ve done nothing to address the problem. Second, and maybe more importantly, is the way the movie made me feel. I’ve already said it was maybe a little void of emotion and that’s true; what I mean is how it made me evaluate my own filters. As sympathetic to the cause as I am, I’m still a white lady, and I experienced the film and the events depicted within it as a white person with all the privilege inherent in those words. The motel scenes are grueling and I had visceral reactions to them. Occasionally I caught myself frustrated with how the characters were responding to the cops, and I’d have to check myself. This is the fundamental takeaway of the film: my experience with police officers is essentially just very, very different. I wasn’t born with a historical fear of cops. My parents and grandparents didn’t raise me to be afraid of them. The colour of my skin protects me from the worst. My entitlement trusts in my human rights. My privilege demands that people in positions of authority will respect my unalienable civil liberties. The last interaction with a police officer I had was the guy directing pedestrians leaving a Cirque du Soleil show. The last time we were pulled over for speeding, there wasn’t so much as an apology uttered for being caught red-handed. These things don’t feel like privilege because they’re things we believe we’re owed, but it is privilege because not everyone gets to feel the same way.

Maybe it’s not perfect, but Detroit asks some difficult questions, which makes it an important film. It’s excruciating because it needs to be, and you need to watch it.

tough and the tender, the blurring of the line between the two. Adi (Adrian Schiop) is a fish out of water, and Alberto (Vasile Pavel), rough as heck around the edges, provides interesting if skewed insight. Soon their companionable partnership turns into something sexual, quasi-romantic. It’s a quite modern gay love story from behind the poverty line and director Ivana Mladenovic’s lens is intimate and gritty.

tough and the tender, the blurring of the line between the two. Adi (Adrian Schiop) is a fish out of water, and Alberto (Vasile Pavel), rough as heck around the edges, provides interesting if skewed insight. Soon their companionable partnership turns into something sexual, quasi-romantic. It’s a quite modern gay love story from behind the poverty line and director Ivana Mladenovic’s lens is intimate and gritty.

Zookeeper’s Wife, and We Bought A Zoo, and more recently I was reading another book about a woman who led an underground railroad of sorts to smuggle Jewish children out of the ghetto, wherein the zookeeper’s wife was specifically mentioned. It was an especially brutal place to be during the war. Terrible, unspeakable things happened every day, and it’s kind of a miracle to see\hear these stories about ordinary people who couldn’t live with what was happening, so they didn’t [it’s sort of awful that these words sound very applicable even today].

Zookeeper’s Wife, and We Bought A Zoo, and more recently I was reading another book about a woman who led an underground railroad of sorts to smuggle Jewish children out of the ghetto, wherein the zookeeper’s wife was specifically mentioned. It was an especially brutal place to be during the war. Terrible, unspeakable things happened every day, and it’s kind of a miracle to see\hear these stories about ordinary people who couldn’t live with what was happening, so they didn’t [it’s sort of awful that these words sound very applicable even today]. pretty soon Chris is fed up with waiting. In the wake of their inevitable breakup, Sonia is inspired by a fellow subway rider’s thong (no I am not making that up, thankyouverymuch) to fly to Italy to find herself, and by herself, I mean some Italian guy’s dick.

pretty soon Chris is fed up with waiting. In the wake of their inevitable breakup, Sonia is inspired by a fellow subway rider’s thong (no I am not making that up, thankyouverymuch) to fly to Italy to find herself, and by herself, I mean some Italian guy’s dick. Bigelow’s treatment of the subject is at a pretty cold remove, for example. And I for one felt it was just too long. The film could have ended when the last person leaves the motel, but instead it follows the white police officers who were charged with felonious assault, conspiracy, murder, and conspiracy to commit civil rights abuse. The courtroom scenes are a long, drawn-out denouement that don’t quite jibe with the first two thirds of the film. That said, I still feel like Detroit is an extremely effective film.

Bigelow’s treatment of the subject is at a pretty cold remove, for example. And I for one felt it was just too long. The film could have ended when the last person leaves the motel, but instead it follows the white police officers who were charged with felonious assault, conspiracy, murder, and conspiracy to commit civil rights abuse. The courtroom scenes are a long, drawn-out denouement that don’t quite jibe with the first two thirds of the film. That said, I still feel like Detroit is an extremely effective film. for the swinging bachelor existence Charlie has planned for them on board, but that’s only half his trouble. A snarky entertainment director is on to them and their little ruse could cost them thousands of dollars that neither can afford (hello, gambling my old friend!) if found out and no amount of Rue McClanahan flirtation can save them.

for the swinging bachelor existence Charlie has planned for them on board, but that’s only half his trouble. A snarky entertainment director is on to them and their little ruse could cost them thousands of dollars that neither can afford (hello, gambling my old friend!) if found out and no amount of Rue McClanahan flirtation can save them. Capturing a thunderstorm, the camera shakes as the cameraperson sneezes.

Capturing a thunderstorm, the camera shakes as the cameraperson sneezes. illnesses, no one’s going to let an emaciated Lily Collins push a fish stick around her plate for dinner. And they’re also very difficult to treat because unlike drinking, you can’t simply give up food. You have to learn to eat in moderation. Eating disorders are often (but not always) about control. Often there is some type of childhood abuse that accounts for someone wanting very much to exert control over their bodies now.

illnesses, no one’s going to let an emaciated Lily Collins push a fish stick around her plate for dinner. And they’re also very difficult to treat because unlike drinking, you can’t simply give up food. You have to learn to eat in moderation. Eating disorders are often (but not always) about control. Often there is some type of childhood abuse that accounts for someone wanting very much to exert control over their bodies now. a) Is it even ethical to “give away” a baby as promotional material?

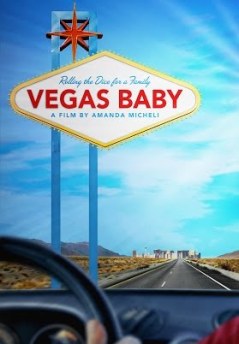

a) Is it even ethical to “give away” a baby as promotional material? Sherwin (David Oyelowo) and Lucinda (Dianne Wiest) knock about in her rural home with only her nurse Ann (Rosie Perez) between them. Lucinda is sick and in a lot of physical pain but she’s not too sick to still be kind of a bitch. The last time she saw her daughter they fought, as usual, and parted badly, both assuming for the last time, and of course it was, only it was daughter who died, and not the ailing mother.

Sherwin (David Oyelowo) and Lucinda (Dianne Wiest) knock about in her rural home with only her nurse Ann (Rosie Perez) between them. Lucinda is sick and in a lot of physical pain but she’s not too sick to still be kind of a bitch. The last time she saw her daughter they fought, as usual, and parted badly, both assuming for the last time, and of course it was, only it was daughter who died, and not the ailing mother. the fun gets spoiled when the stripper gets accidentally murdered, and the hen party suddenly has to hide the dead rooster. The situation is wildly implausible and uncomfortably phony. Some have complained that the script focuses more on comedy than on story, and while I agree that story was largely absent, so were the jokes. I don’t think I laughed once, and I love me some Kate McKinnon.

the fun gets spoiled when the stripper gets accidentally murdered, and the hen party suddenly has to hide the dead rooster. The situation is wildly implausible and uncomfortably phony. Some have complained that the script focuses more on comedy than on story, and while I agree that story was largely absent, so were the jokes. I don’t think I laughed once, and I love me some Kate McKinnon.