I mean, who’s NOT excited to see a film adapted from a 784 page, Pulitzer-prize winning novel about a missing piece of art? Sean Taylor, that’s who. He did, however, make use of the film’s 147 minute run time to have a hearty nap. Hands lightly clasped, mouth totally agape, he slept, and he slept hard, for 60 of the film’s first 65 minutes. So when he did wake up, I wondered what the point was in staying. Surely he was lost. Surely there would be no rejoining the movie at this point.

But the truth is, wide awake as I was and always had been, I wasn’t any more into it. And yes, I had read Donna Tartt’s novel, which has been bowing my bookcase ever since.

The Goldfinch is about a little boy who visits a museum with his mother, who then perishes when the museum is bombed in a terrorist attack. Having survived the bombing, young Theo (Oakes Fegley) wanders around the ruins, searching for his mother, until an old man stops him, and with his dying breath, implores him to take a painting, Fabritius’ The Goldfinch.

Basically orphaned, Theo is sent to live with classmate’s family (Nicole Kidman plays the mother). He befriends the old man’s business partner, Hobie (Jeffrey Wright) and another young survivor, a cute redhead named Pippa, who sustained brain damage in the attack. But just as he’s maybe settling into this new, motherless life, his deadbeat dad (Luke Wilson) shows up, with a surprise girlfriend (Sarah Paulson) in tow, and whisks him off to live in a deserted Vegas suburb of foreclosed homes. His only friend is a boy named Boris (Finn Wolfhard), who’s got some questionable habits, though not nearly as objectionable as his dad’s, as it turns out.

Cut to: adult Theo (Ansel Elgort) is an antiques dealer, working with Hobie in New York City, trying his best just to cope with the lingering effects of the attack, trying hard not to be held hostage by the trauma. He’s held onto this painting, a very historied and valuable painting, all these years, secretly of course, allowing the rest of the world to believe this priceless artifact was destroyed in the bombing along with so much else. But that is not the case.

Can you imagine what this painting might represent to a young orphaned boy, having saved it from the very same rubble in which his mother’s body lay? Director John Crowley cannot. In 2.5 hours, the painting is not a symbol of hope, or a replacement parent, or the receptacle of grief and loss. It’s just a dead thing underneath a kid’s bed, as if it means nothing. In fact, the movie itself means nothing, but it takes an agonizingly long time establishing this nothingness. On and on, with lots of things happening yet none of it finding meaning. And worse yet, it finds no emotional connection, nor does it appear to even look for it. And when you’re talking about childhood trauma and absentee parents and feelings of dread and loneliness – well, you’ve got to be pretty bad at your job not to even accidentally stumble upon some kind of feeling.

The painting The Goldfinch is about how we preserve meaningful bits of our lives and our culture, but the movie The Goldfinch is about how some things are destined to be forgotten.

of the novel by Camilla Gibb, and of course I read it myself about 500 books ago. I have little memory of it, but had the vague impression of not having appreciated it much.

of the novel by Camilla Gibb, and of course I read it myself about 500 books ago. I have little memory of it, but had the vague impression of not having appreciated it much. Jamie’s dad, Quint (Peter Sarsgaard) just happens to be the manager of that hedge fund I was talking about, and he’s super stressed, selling assets to stop the bleeding. He’s not a particularly nice guy, it probably goes without saying. His wife Karen (Marisa Tomei) is fairly pragmatic about their flawed marriage, but she cries a lot. She recently bought a theatre to renovate and run, but with the hedge fund having a coronary, she’s about to lose it.

Jamie’s dad, Quint (Peter Sarsgaard) just happens to be the manager of that hedge fund I was talking about, and he’s super stressed, selling assets to stop the bleeding. He’s not a particularly nice guy, it probably goes without saying. His wife Karen (Marisa Tomei) is fairly pragmatic about their flawed marriage, but she cries a lot. She recently bought a theatre to renovate and run, but with the hedge fund having a coronary, she’s about to lose it. cuppa, not by a long shot. As an introduction to this film’s premiere at TIFF, Iannucci informed/assured us the two films could not be more different. And while I’m not sure that’s true, I was relieved and elighted to find myself really enjoying it.

cuppa, not by a long shot. As an introduction to this film’s premiere at TIFF, Iannucci informed/assured us the two films could not be more different. And while I’m not sure that’s true, I was relieved and elighted to find myself really enjoying it.

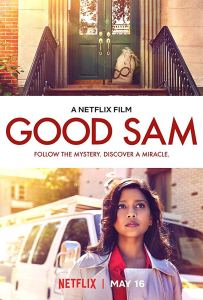

Kate, who started off reluctant to report on something so negligible, now has quite a story on her hands. And it’s not just that it’s something positive making the news for once. It’s the mystery of the thing. Who is this guy, who becomes known in the media as Good Sam, short for good samaritan, and why is he changing lives without taking credit? Kate is obsessed with but skeptical of the notion that someone might be doing good without expecting anything in return – is this naiveté, or wishful thinking, or a new kind of philanthropy set to inspire a whole city?

Kate, who started off reluctant to report on something so negligible, now has quite a story on her hands. And it’s not just that it’s something positive making the news for once. It’s the mystery of the thing. Who is this guy, who becomes known in the media as Good Sam, short for good samaritan, and why is he changing lives without taking credit? Kate is obsessed with but skeptical of the notion that someone might be doing good without expecting anything in return – is this naiveté, or wishful thinking, or a new kind of philanthropy set to inspire a whole city? exactly those issues in better movies than this a hundred times before. And Williams just doesn’t have the allure of Johnny Cash or the talent of Ray Charles or the magnetism of James Brown. He’s just an entitled white dude who made life rough for himself. He made some music and then he died. Hank Williams may be a legend, but you’d never know it from this movie. It makes him seem banal and tiresome. And that’s gotta be hard to do to a man known as the King of Country Music, influencer of Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan, prolific song writer, winner of a posthumous Pulitzer for craftsmanship.

exactly those issues in better movies than this a hundred times before. And Williams just doesn’t have the allure of Johnny Cash or the talent of Ray Charles or the magnetism of James Brown. He’s just an entitled white dude who made life rough for himself. He made some music and then he died. Hank Williams may be a legend, but you’d never know it from this movie. It makes him seem banal and tiresome. And that’s gotta be hard to do to a man known as the King of Country Music, influencer of Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan, prolific song writer, winner of a posthumous Pulitzer for craftsmanship. terminally popular and super-rich Shelby (Camila Mendes), and he gets an idea for a business opportunity. He’s going to need a lot of money to pay for Harvard (and to woo Celia), so why not rent himself as a date for hire? It worked well enough the first time, with Shelby, so why not with other girls? He recruits best friend Murph (Odiseas Georgiadis) to set up a dating app, one where girls can choose what date he’ll take them on, what outfit he’ll wear, what topics he’ll discuss, even what personality he’ll embody.

terminally popular and super-rich Shelby (Camila Mendes), and he gets an idea for a business opportunity. He’s going to need a lot of money to pay for Harvard (and to woo Celia), so why not rent himself as a date for hire? It worked well enough the first time, with Shelby, so why not with other girls? He recruits best friend Murph (Odiseas Georgiadis) to set up a dating app, one where girls can choose what date he’ll take them on, what outfit he’ll wear, what topics he’ll discuss, even what personality he’ll embody.